Preserving Some History:

Before the time of sorbates, nitrates, and refrigerators with climate-controlled produce drawers, processes to extend the shelf life of fresh foods were limited. While salting and curing worked well for meats, preservation of fruit posed a cornucopia of difficulties because of their delicate tissues, sweet flavor, and rapid rate of decomposition.

Several societies around 6000 BCE successfully preserved fruit by submerging it in honey, which is valuable for its antimicrobial compounds in addition to its flavor. Sugar solutions replaced honey in many European cuisines in the 17th Century when sugar trade was jumpstarted from the Caribbean Islands.

However, the first (almost) completely safe method of fresh fruit preservation was canning. One could say that Napoleon Bonaparte is responsible for its invention, because he commissioned the project: 12,000 francs to anyone who invented a technique to keep food hydrated and delicious for his hungry troops. However, the real brain behind the operation was Nicolas Appert, a confectioner and distiller who developed the canning process for France around 1800.

Canning:

Image from pickyourown.com

The general steps of canning include:

- Putting contents into a sterilized, lidded jar.

- Heating the mixture to a boiling temperature.

- Cooling.

Covering the jar prevents bacteria from entering the system and boiling raises the mixture to 212°F+, a temperature threshold that destroys most microorganisms. Additionally, because oxygen gas molecules are small and not very dense, the heating process forces them to escape the unsealed lid. This creates an anaerobic environment inside the jar, inhibiting growth of any remaining bacteria that consume oxygen.

As the contents’ temperature decreases during the cooling process, condensation of gas particles to their liquid state decreases pressure within the jar, creating a vacuum that pulls down the lid and seals its rubber gasket to the glass rim.

Sugar Content in Jam:

Most jams have a 1:1 mass ratio of fruit to sugar, although several sources recommend using a 2:3 ratio for best results. This is indubitably a lot of sugar, causing many amateur jammers to try and reduce its quantity, replace it with an artificial sweetener, or otherwise go off the rails to avoid excessive consumption of calories. However, jam is one of the many foods that loses its essential culinary properties when it is modified to become “healthier”. In addition to further inhibiting bacteria growth (surprising, I know), adding a large quantity of sugar assists essential structural elements to make jam’s unique texture.

Mediocre strawberry-apricot jam, made by yours truly.

With the goal of killing microorganisms, drenching fruit in a highly saturated sugar solution seems counterintuitive. Many yeast and bacteria love to eat sugar! However, by establishing a higher concentration of sucrose outside the cells, water flows down its concentration gradient and out of the microorganism’s cytoplasm, dehydrating them to the point of death.

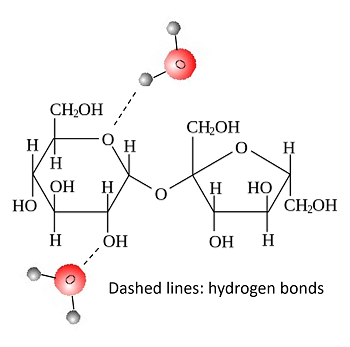

Additionally, sugar binds to excess water in jam via its polar hydroxyl groups (OH), preventing the growth of bacteria that depend on water. This also allows a final ingredient in jam, a polysaccharide called pectin, to create a gel network.

Sucrose attracting water molecules. Image by Justin Wiens

Sucrose attracting water molecules. Image by Justin Wiens

The Pectin Gel Network:

Pectin exists naturally in the cell walls of fruit and is released during the boiling process. However, it is commonly added in dried/crystal form to supplement low-pectin fruits.

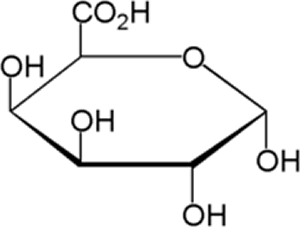

A gel network is a solid that holds pockets of liquid. When pectin monomers (polygalacturonic acid) bind to other pectin monomers, it makes a solid structure to hold the other components of jam, resulting in a thick, spreadable texture.

Polygalacturonic acid. Image by dynamicscience.com

A proper pectin gel is difficult to create. Pectin monomers have carboxyl groups (COOH), which are polar atom configurations with a high affinity for water (which is also polar). In environments with excess water, pectin monomers are diluted, making it difficult for them to create a continuous chain. This is why the best jam recipes require sufficient amounts of sugar to bind with water (and let water evaporate during any initial boiling processes).

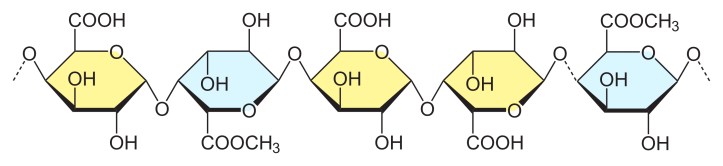

A pectin chain. Some carboxyl groups (COOH) in polygalacturonic acid monomers have been methylated to form COOCH3. This is enhances its gelling properties. Image by silvateam.com

An added textural complication is pectin’s behavior as a base. Its monomers lose a H+ ion when dissolved in water, causing them to accumulate a negative charge. Monomers with the same charge repel each other and make it difficult for the pectin to form a continuous chain. To mitigate this, an acid is added to jam. The acid donates H+ atoms to the monomer molecules, neutralizing their negative charge and allowing them to bind to each other. However, too much acid can create a gel network that is too stiff and “weeps” liquid, so it is important to measure your lemon juice carefully!

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

“Food Chemistry -Carbohydrates-Pectin.” Biology-Nervous System-Response Time Research, http://www.dynamicscience.com.au/tester/solutions1/chemistry/foodchemistry/pectin.htm.

“Home Canning & The History Of Canning | THE NIBBLE Blog – Adventures In The World Of Fine Food.” The Nibble: Brownies History, http://www.thenibble.com/blog/2012/08/11/tip-of-the-day-home-canning-for-fun/.

“Jam: a Beautifully Preserved History.” Spectator Life, 21 Oct. 2016, life.spectator.co.uk/2016/10/jam-beautifully-preserved-history/.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking the Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner, 2004.

Nummer, Brian A. “Historical Origins of Food Preservation.” National Center for Home Food Preservation | How Do I? Can Fruits, 2002, nchfp.uga.edu/publications/nchfp/factsheets/food_pres_hist.html.

Ward, Christina. “Tomatoes, Acid, and Heat: The Science of Canning.” Serious Eats, Serious Eats, http://www.seriouseats.com/2017/09/how-to-heat-pressure-steam-can-tomatoes-preserve.html.

Weins, Justin. “Chemicals & Solubility In Water: Interactions & Examples.” Study.com, Study.com, study.com/academy/lesson/chemicals-solubility-in-water-interactions-examples.html.

“What Makes Jam Set? – The Chemistry of Jam-Making.” Compound Interest, Compound Interest, 11 July 2015, http://www.compoundchem.com/2014/09/22/what-makes-jam-set-the-chemistry-of-jam-making/.

Very interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person