Maybe it was an unexpected kick of cayenne pepper in Grandma’s casserole, or a jalapeño hidden under layers of daikon and tofu in a bahn mi. Perhaps you didn’t strain your homemade chicken stock and accidentally bit into a black peppercorn. In any case, your mouth feels like it is on fire — and it wasn’t because your meal had a particularly high temperature. What contributes to our perception of food, and how can chemicals confuse our feelings of pain and pleasure?

An Overview of the Chemical Senses

Taste:

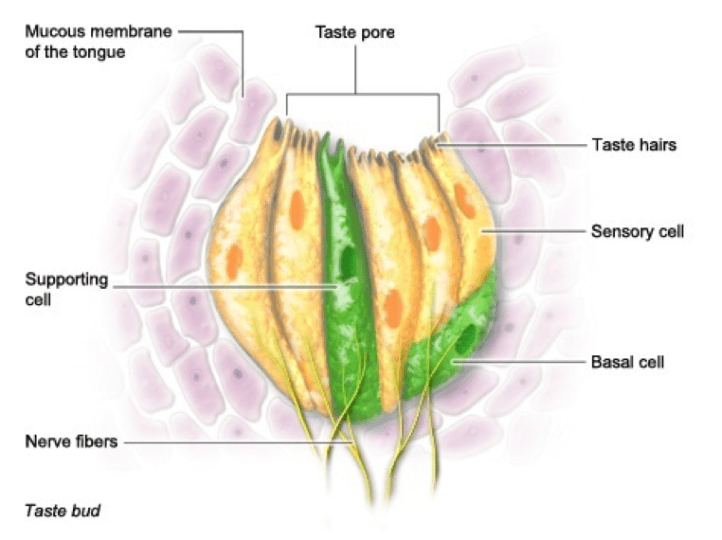

Taste, or gustatory perception, is the chemical sense most commonly associated with eating. The food we consume decomposes into simpler substances with the help of salivary enzymes, allowing specific molecules to bind to sensory cells in taste buds. The taste buds’ sensory cells communicate with nearby sensory neurons, triggering action potentials that reach the brain. From here, the brain can produce a variety of responses, including the release of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that makes you feel happy and helps digest food.

Sensory cells connected to sensory nerve fibers. Image from the N.I.H.

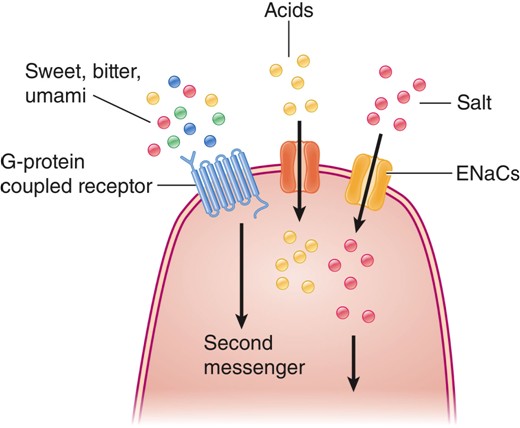

Humans can distinguish between 5 categories of “taste” chemical interactions: sweetness, bitterness, umami (savory-ness), sourness, and saltiness. Sweetness, bitterness, and umami tastes are triggered by molecules binding to various G-Protein coupled receptors in taste bud cell membranes. Sour taste originates from H+ ions diffusing through taste cell membranes. Saltiness comes from alkalai metals entering taste cell membranes through ion channels, the most notable example being sodium ions (Na +) from table salt (NaCl) passing through sodium channels.

Tastants and a Receptor cell. Image from Kip McGuillard.

Scientists debate whether individual taste buds have the ability to detect all five basic tastes with an emphasis on one, or if they can only detect one type of taste. However, they agree that collective signaling from taste sensory cells and sensory neurons is required to create an appreciable reaction from the brain.

Smell:

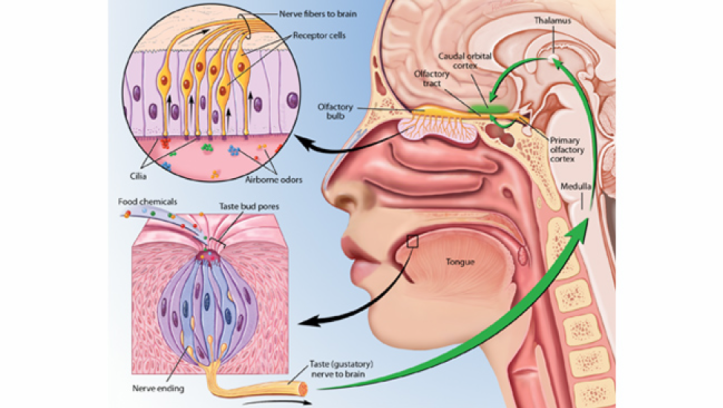

The majority of our flavor detection is actually perceived by a different chemical sense: smell, or olfaction. Quantitative estimates suggest that around 80% of what we call “taste” comes from our smell, although this percentage is difficult to pinpoint due to inevitable overlap of gustation (taste through tastebuds) and olfaction processes.

Olfactory influences range from exterior odors, such as volatile (gaseous) molecules wafting off food while it is still on the fork, to interior release of odors: volatile molecules being liberated during the chewing process. The mouth is connected to the nose via the larynx, which allows gaseous molecules to reach sensory neurons in the nose. Here, they bind to receptors and trigger action potentials in nerves that reach the brain, evoking responses similar to those triggered by taste buds.

Summary of how smells and tastes reach the brain. Image from BrainFacts.

Chemesthesis:

Some foods do not have a strong taste but elicit a distinct feeling in the mouth.

For example, Sriracha makes the mouth feel hot and pleasantly irritated, while mint cools and sooths the mouth. This response is the result of chemesthesis: the sensitivity of skin and mucous membranes to chemicals. Tolerance for different chemicals varies across the body, but in the mouth, two families of pungent molecules, alkyl-amides and thiocyanates, trigger the same receptors as high temperatures, pain, and touch. When action potentials are triggered in these sensory neurons, the brain responds by increasing blood flow to the site, and releasing pain induced endorphins (happy hormones).

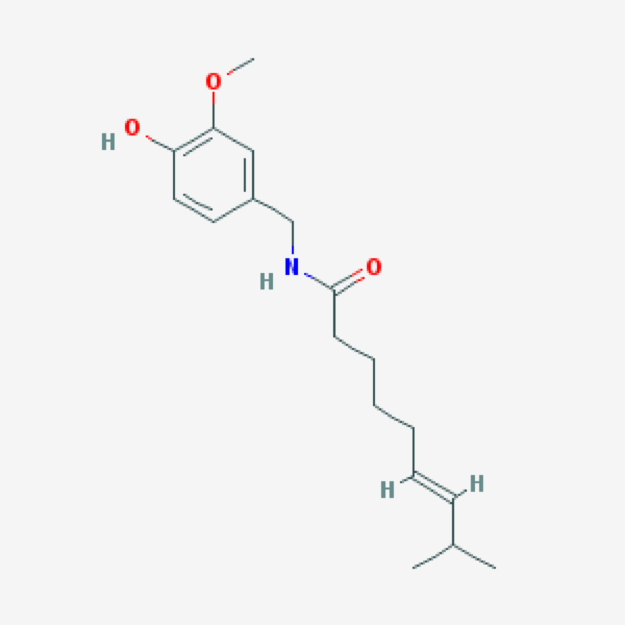

Found in spicy peppers, alkyl-amide molecules are so heavy (40-50 atoms) that they only activate sensory neurons in the mouth, not those in the olfactory system (it is too difficult for them to become gaseous and travel up to the nose). The most prevalent and potent alkyl-amide is capsaicin, which is found in chillis.

Capsaicin Molecule. Image from the N.I.H.

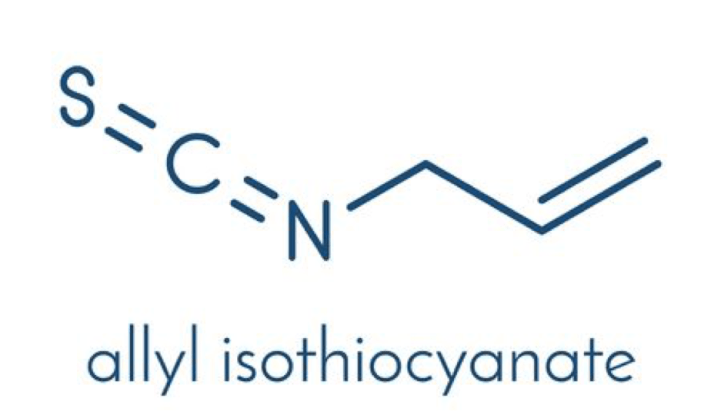

Thiocyanate molecules, found in mustard and horseradish, are much smaller (12-24 atoms) and thus are able to trigger pain receptors in both the mouth and the nose.

Allyl isothiocyanate is the primary thiocyanate in mustard, wasabi, and radishes. Image from Wikipedia.

Quantifying Spice: Scoville Heat Units

In 1912, an American pharmaceutical chemist named Wilbur Scoville developed the Scolville Organoleptic Scale for measuring spiciness of different chillis. I have summarized his procedure below:

- Using alcohol, extract capsinoids from a standard mass of pepper.

- Combine capsinoids with a mixture of sugar and water

- Feed to a panel of 5 tasters.

- Gradually dilute sample with water until 3/5 tasters can no longer detect “pungency”.

- Record the degree of dilution as the pepper’s Scoville Heat Units (SHUs)

There are several flaws with this system. First, capsinoid concentration within a single pepper species can vary widely due to growing location, access to sunlight, and plant age. Without multiple pepper sources and trials, it is impossible to create a repeatable experiment. Second, human detection of this capsinoid concentration, or “pungency” is variable. Even trained tasters will experience differing degrees of sensitivity and irritation in their mouths after consuming concentrated capsinoid solutions. As the solutions become more and more dilute, it becomes difficult to decide whether new capsinoid presence or lingering capsinoids are the source of tingling in the mouth.

High performance liquid chromatography has begun to update the Scolville scale for these reasons. Using this method, the majority of capsaicinoids (capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin) can be evaluated quantitatively instead of empirically.

Pungency of a few Chillis**

| Chilli | Scoville Heat Units |

| Bell | 0 – 600 |

| Paprika | 0 – 2,500 |

| Jalapeño | 2,500 – 10,000 |

| Serrano | 10,000 – 25,000 |

| Cayenne | 30,000 – 50,000 |

| Tabasco | 30,000 – 50,000 |

| Habanero | 80,000 – 150,000 |

More pungent chillis are diluted more times, giving them a higher number of Scoville Heat Units.

**Chilli? Chili? Chile? Chill out. I’ll explain how we arrived at all of this confusing spelling and ambiguous terminology. The native Nahuatl word for a hot, spicy pepper is “chilli”. The Spanish turned this into “Chile” and Americans turned “chile” into “chili”. Now for double meanings. The country "Chile" has nothing to do with peppers; is the Aurucanian word for “end of the earth”.The American stew/soup chili is named for the capsaicin-containing powder you used to make it. Although it isn’t the most common spelling today, many food scientists prefer to use “chilli” when describing pungent peppers because it is the original word, and because there is no question as to what it is referencing.

How to Reduce Spiciness (Before and After Eating):

Contrary to popular belief, the majority of capsaicinoids are not found in pepper seeds! 80% of Capsaicin is actually found in the placenta, the spongy white tissue that holds the seeds. If you want to be conservative with your chilli flavoring, scoop out the placenta before adding pepper to your dish.

If the damage has been done and you already ate something too spicy, how can you get rid of the burning feeling? Capsaicin, and most other pungent molecules, are nonpolar. This means they will dissolve in nonpolar liquids, such as alcohol. Although beer’s 5% alcohol is not enough to wash them off your tongue, tequila’s 40% works much better.

Even if you ARE legally allowed to drink alcohol, it turns out that dairy products work best as a spice scrubber. Their casein protein molecules have hydrophobic (non-polar) tails that dissolve capsaicin oils much like soap dissolves oil.

Sources:

Charles Spence. “Just How Much of What We Taste Derives from the Sense of Smell?” Flavour, BioMed Central, 2 Nov. 2015, flavourjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13411-015-0040-2.

Flatow, Ira. “Smell Science, Reader Come Home, Sonar Smackdown.” Science Friday, 16 Nov. 2018.

Glass, Don. “How Do Chili Peppers Make Your Mouth Feel Like It’s On Fire?” StateImpact StateImpact Indiana, indianapublicmedia.org/amomentofscience/chili-peppers-mouths-on-fire/.

Green, Barry. “Why Is It That Eating Spicy, ‘Hot’ Food Causes the Same Physical Reactions as Does Physical Heat (Burning and Sweating, for Instance)?” Scientific American, John B. Pierce Laboratory, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-is-it-that-eating-spi/.

“How Does Our Sense of Taste Work?” Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 17 Aug. 2016, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279408/.

McGee, Harold. McGee on Food and Cooking: an Encyclopedia of Kitchen Science, History and Culture. Hodder & Stoughton, 2004.

McGuillard, Kip. “Chapter 6 Sensory Physiology Sections.” Evolution and Roles of Senses. 4 Jan. 2019, Eastern Illinois University.

Purves, Dale. “The Chemical Senses.” Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1970, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10864/.

“The Scoville Scale. How to Measure the Heat of Chilli.” Seatonfire Chilli Chocolate, 4 Dec. 2015, http://www.seatonfire.com/news/2015/12/4/the-scoville-scale-how-to-measure-the-heat-of-chilli.

Vandergriendt, Carly. “What’s the Difference Between Dopamine and Serotonin?” Healthline, Healthline Media, http://www.healthline.com/health/dopamine-vs-serotonin#other-psychological-conditions.

Wolke, Robert L., and Marlene Parrish. What Einstein Told His Cook 2: the Sequel: Further Adventures in Kitchen Science. W.W. Norton, 2005.