Today as I was chopping some dark chocolate with a butcher knife, I noticed that big pieces kept rising to the top whenever I swept the pile back together. This was frustrating because I only wanted to cut up the large chunks, and it’s a lot easier if they’re on the surface of the cutting board instead of a slippery pile of chocolate shavings.

My observation seemed counterintuitive; I thought the biggest (and presumably heaviest) pieces of chocolate would sink to the bottom or tumble down the sides of the pile. Why does this phenomenon happen?

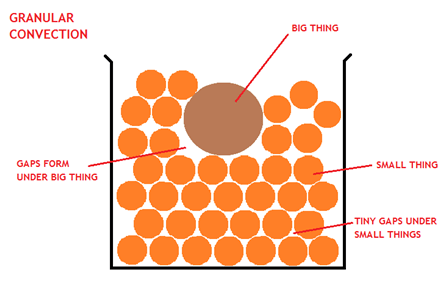

After doing a bit of research and staring at my chocolate pile for a while, it looked like small pieces were falling through the spaces between the larger ones, and in doing this “pushed” the larger particles up. This makes sense; having less air space toward the bottom of the pile lowers its center of mass and is energetically favorable (we assume here that the chocolate pieces from the same bar are of equal density).

This is part of a concept called granular convection. It is especially pronounced in particle sorting with objects in a container. When shaken, vibration induces convective flow (a similar pattern to that seen in heated liquids). The big particle rises up through the center of the mixture and smaller particles fill its previous space, inhibiting sinking. When the big particle reaches the surface, it doesn’t have space to flow back down along the sides, or can’t overcome frictional forces, so it just sits there.

The Brazil Nut Effect

This separation of particle sizes—larger on top, smaller on the bottom– is called the brazil nut effect. I think it’s an excellent name. Just think of a container of Costco mixed fancy nuts and how the top of the container is always scattered with brazil nuts (the largest nut of the mix). I also think of buying granola, and how the bigger pieces are at the top of the bag.

Many factors affect the strength of the brazil nut effect (and whether it occurs at all), such as height of the container, friction of walls (more friction seems to increase separation because it inhibits large particle sinking), density of particles, diameter of particles, diameter to density ratio of particles, etc. There are over 10 mechanisms to explain the effect, and most are explained by a trade-off domination between inertia and convection. In D. A. Huerta and J. C. Ruiz-Suárez’s findings, inertia dominates when relative density is greater than one, and convection dominates when relative density is less than one. Later studies add that size, in addition to density, is a factor that must be considered separately.

Results are inconsistent on many fronts. Often, the same experiment model– vibrating glass tubes with a mixture of 2 different sized or dense particles—produces inconsistent results when replicated. Studies agree, however, that the larger the particle, the faster it will rise through a vibrating bed (all else remaining constant). Most also agree that lighter particles rise more quickly.

Figure from D. A. Huerta and J. C. Ruiz-Suárez’s article, showing lighter (lower relative density) particles rising in less time. Heavier (higher relative density) particles sink in less time.

Beyond Trail Mix

Applications of these findings, and their inconsistencies, are many. It could explain the shapes of containers packaged goods come in. Less surface area, and therefore less opportunities for friction, means we see cylindrical containers over rectangular ones for many mixed nuts and fancy granola bags. In New England geology, granular convection explains the seemingly never-ending flow of large rocks to farm topsoil every year. It also explains the inverse graded bedding that occurs in formerly glaciated areas. Inverse graded bedding, with smaller clay and silt particles below large clasts, can cause favorable conditions for mudslides and other catastrophic natural events.

Overall, there is much still to be understood about the interplay between size and density, sinking and falling. We live in a world filled with heterogenous mixtures—it would benefit everyone to understand their dynamics more fully.

Works Cited

“Granular Convection.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Mar. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Granular_convection.

Huerta, D. A., and J. C. Ruiz-Suárez. “Vibration-Induced Granular Segregation: A Phenomenon Driven by Three Mechanisms.” Physical Review Letters, vol. 92, no. 11, 2004, doi:10.1103/physrevlett.92.114301.

Shinbrot, Troy. “The Brazil Nut Effect – in Reverse.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, May 2004, http://www.nature.com/articles/429352b.

Spector, Limor S. “The Reverse Brazil Nut Effect in Granular Flow: Nutty or Not?” Professor Robert B. Laughlin, Department of Physics, Stanford University, 10 Dec. 2007, large.stanford.edu/courses/2007/ph210/spector2/.

Toshihiro Chujo, Osamu Mori, Junichiro Kawaguchi, Hajime Yano, Categorization of Brazil nut effect and its reverse under less-convective conditions for microgravity geology, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 474, Issue 4, March 2018, Pages 4447–4459, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stx3092